COMPASS Initiative® Funds 32 Organizations to Transform the HIV Epidemic in the South

Atlanta, Georgia (November 30, 2018) – In recognition of the 30th anniversary of World AIDS Day and in support of

By: Haneen Elfaki

March is a month of celebration and recognition for women around the world. It marks Women’s History Month, where we honor and recognize the immense contributions of women throughout history. Additionally, March 10th is National Women and Girls HIV/AIDS Awareness Day – a day to raise awareness about the disproportionate impact that HIV/AIDS has on women and girls.

On this day, we show our support for those living with HIV/AIDS by educating ourselves on how it affects not only individuals but also entire communities. We can also take action to end stigma associated with HIV/AIDS by speaking out against discrimination or providing resources to help those affected access education and treatment options. By doing so, we are helping create an environment where everyone can live their best life without fear or shame due to their status or identity.

It is also important to pay attention to the ways in which HIV/AIDS disproportionately affects women and girls. Women are at a greater risk of contracting HIV due to biological, economic, and cultural factors. Additionally, they often face barriers such as stigma and discrimination when it comes to accessing testing, treatment, and preventive measures. It’s important to raise awareness about the challenges that women and girls living with HIV/AIDS face so we can work together to provide them with better care and support.

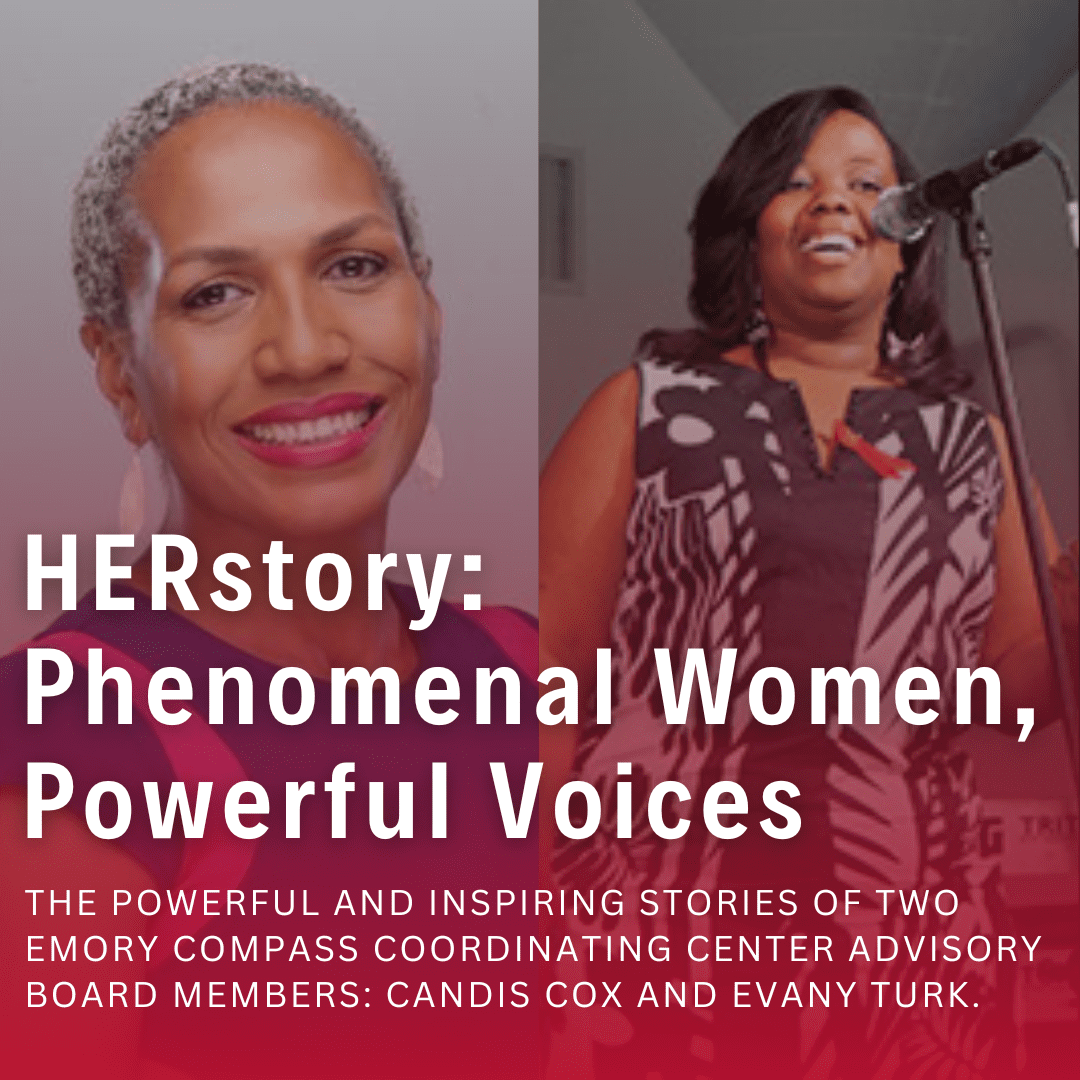

To further exemplify this, we want to highlight two phenomenal women from the Emory COMPASS Coordinating Center’s Advisory board, Candis Cox and Evany Turk. These powerful women were interviewed to share their story and work on HIV/AIDS. Their accounts are a reminder of how many people are facing challenges related to HIV/AIDS and what we can do to support them. They also provide a unique perspective on how we can work together to create an environment where everyone — regardless of their status or identity — has the opportunity to live a healthy and safe life.

Candis Cox

Candis Cox is a Black, heterosexual, transgender woman originally from Syracuse, New York and now relocated to Charlotte, North Carolina. Candis is a gender and sexuality educator, speaker, and advocate for the LGBTQ+ population in her community of Charlotte, North Carolina and throughout the United States. She has been a guest speaker and featured on numerous news channels to educate the public and raise awareness on issues that face the transgender, LGBTQIA+, women and minority communities throughout the United States.

“I do this work because I was taught early on that education is power and the one thing that once you have it, it sets you apart from the rest”

Evany Turk

Evany Turk is a black, heterosexual, cisgender woman originally from Chicago, Illinois and now living in Texas. Evany is a national HIV consultant with over 15 years of experience advocating for and working with various HIV/AIDS-related public health initiatives and programs. In 2021, she started her own consulting firm, Heartworks Consulting, to consult agencies, public health departments, and community-based organizations to work on specific programming for women living with HIV.

“I believe if we reach and get all of the women living with HIV the care they need, that we help everybody”

Here are their stories:

HE: Tell me a little bit about yourself, where are your roots from?

CC: I’m originally from Syracuse, New York. I was a surprise baby for my mother while she was in college. I am half Black and half Puerto Rican. I moved around a lot. My mom when I was eight years old, went back to college, and then medical school and then residency. So, I’ve moved all over and lived all over. My mom’s family is from Louisiana, Alabama. We still own our land down there, that’s where my heart is. I attended North Carolina Central University and North Carolina State University. Now, I live in Charlotte, North Carolina with my husband and our family.

ET: I was born and raised in Chicago. I was born into a big family of a lot of very strong women with roots from Mississippi, which I visited a lot. I’ve been living with HIV for 20 years. I have two children, two boys an 18 year old and a 30 year old; one of them I had through living with HIV. We moved south to Texas six years ago and, you know, just raising my kids and working. I’ve been working in the HIV field for about 16 years. And I’ve done pretty much everything from housing to prevention, policy and advocacy. I’ve even opened up a new center for LGBTQIA+ youth.

HE: How long have you been engaged in HIV/AIDS work? What inspired you?

CC: Since birth. My great uncle, who I idolized, contracted the virus and the first wave before we knew what it was. He and his partner both contracted it. Our family was very close and very community involved. So, I started [in HIV/AIDS work] as early as I can remember. Doing educational seminars where he would go and speak to health care providers about the virus, especially when we didn’t know much. Were Catholic, and he worked a lot with the church and catholic charities because that’s who my grandmother [his sister] worked for. He worked a lot with them and helped to broaden access to people with HIV/AIDS, and I was right there alongside him. When I got older, I started going with my uncle to his infusion treatments. And just seeing how back then, difficult everything was, and how little resources there were. I mean, he couldn’t work back then while receiving all these infusions and everything. It was the same kind of stuff that people who receive cancer treatment get. It took a toll on his body and yet, he couldn’t easily and readily get things like food stamps or housing aid and things like that. And I just thought like, that’s just not a quality of life.

ET: I was diagnosed with HIV in 2001 and struggled with it for about 5 years, until I became pregnant. When I was first diagnosed, I left Chicago to move to Birmingham, Alabama because I was running away from my HIV diagnosis. I didn’t want anybody to know. I lived there for a few years and when I got pregnant, the doctors in Alabama told me I was going to die if I didn’t take my medicine, which I couldn’t take my medicine because I had extreme morning sickness, or if I got an abortion that I would die because my body was so weakened. I didn’t want to accept that I was going to die, so I called my doctors in Chicago and went back home. Thankfully when I returned home, I got the treatment that I needed. I just decided to stay in Chicago because my pregnancy was very hard, and I needed family support. So, I stayed in Chicago and my family found out that I was HIV positive, and it turned into an argument that led to me being homeless. Amid my homelessness, I was introduced to an organization called Chicago House. They gave me an apartment, which got me out of homelessness. Once I got housed, I started volunteering and doing educational activities around HIV. This eventually led me to making a video for the hospital that helped me deliver my baby healthy. Chicago House, saw that video and they reached about a position they had open for a person with experience working in administration and living with HIV. They thought I would be perfect for this position, so I applied and got it. I never imagined working in HIV, but I had started learning a lot about it and so now the place where I lived, I now worked. I started my career in housing, but it was specifically to help people stay adherent to their medication

HE: What differences in healthcare access and treatment have you noticed between Northern states and Southern states?

ET: Absolutely, the Alabama HIV clinic doctors were fine, I feel like I had good care there. The problem came when I went to the maternal health clinic, I experienced a lot of stigma from the nurses and doctors. I was told I was going to die multiple times if I didn’t take my medicine and was discouraged from getting an abortion. The care at the maternal health clinic was nothing like I’ve ever received before it was bad, it was not quality care. So, sitting in that clinic, feeling defeated, I decided it would be best for me to go back to Chicago. Luckily, I still had my social workers number and she said, ‘however soon you can be here we can get you in’. It was easy access, easy appointments, I felt confident in the care and advice that they were giving me. They were affirming, positive about my situation, and even told me that what I’m going through is normal. Now comparing that to the clinic in Birmingham, they were negative, very stigmatizing. Their practices were very old-school in their thinking, they were very behind in their medical practice. Chicago was more advanced, more understanding. Getting into care was very easy. Getting the things that I needed from there was very easy. Even getting the housing was from that from that same social worker, when she found that I was homeless, she connected me immediately to housing. So, way more resources.

HE: What resources were accessible/available at the time to support HIV/AIDS?

CC: This was the early 80s, there just wasn’t. Outside of like Johns Hopkins or the Mayo Clinic or outside of a couple of higher education research schools that were pretty much unattainable. There wasn’t like, maybe the hospital that you were at had an AIDS wing, but it was less about receiving care and more about preparing for them to die. Like back then there weren’t life sustaining services. Because you didn’t live. Just the language the words that we say were different. I mean, back then it was. It wasn’t HIV until you were full blown getting lesions. And once they become visible, that’s the death nail in the coffin.

HE: What are some barriers in the world of HIV/AIDS (then and now)? How do you work through these barriers?

CC: Stigma I think that’s the biggest barrier is stigma around having it, for minority communities especially, it is still seen as a dirty disease. Because having it means you did drugs, you are promiscuous, and you are nasty and dirty. And that stigma is still there, I think that’s a huge barrier because when you’re ashamed of something, you’re not actively seeking aid and looking for your resources and all that, like, you’re just ashamed, unfortunately. And then the unnecessary complications with receiving aid, like, in general we should give aid period, whatever it is, whoever needs it. The system makes it so difficult for people to get it.

ET: I think that there are some providers in the South that aren’t updated as often as they should, on medical advancements for people living with HIV or HIV in general. That is probably one of the biggest barriers to care for people living with HIV. The information is there, if they want it, they should be able to find it, but of course, stigma and people’s perceptions, people’s internal biases in itself has a lot to do with it. They have the thought process that if you’re HIV positive, you shouldn’t be happy, safe, having unprotected sex, etc. Also, a lot of them won’t talk freely about sex to you. So, I think those are some of the issues and barriers to quality care in the South.

HE: How has southern culture impacted or influenced the extent of stigma in HIV/AIDS work? What can be done to reduce stigma in these conversations?

CC: Well, in a lot of ways, so. I can’t remove the lens of race from anything that I talk about. And I feel as though when we’re talking about anything negative when anybody’s talking about it, they’re talking about it through the lens of a minority. Because the white experience is just so different, I mean, they may experience stigma, but the barriers to care and education are not the same as minority populations. Southern culture is so rooted in racism that feeds into stigma of HIV/AIDS, especially since the black population suffers from the virus in such a high rate, especially in the south. And then, I mean, how are you even going to get PrEP? In order to receive PrEP, you must have a prescription and to receive a prescription you must see a doctor, but to see a doctor you must have health insurance. There are people in my family working that still don’t have health insurance. Plus, as minorities, we are not conditioned to go to the doctor, because of the distrust in the healthcare system, especially in the South.

ET: Stigma in the south is different than what I’m used to in the North. I haven’t done anything much different than I was doing up North. I think what people in the South had to get used to was me speaking up and being direct that. I think that helps move the conversation along because when one speaks up, that gives permission for other people to speak up or to support the other people who are speaking up. I’m here to bring whatever resources I have when they’re trying to speak up and support them ahead of that. I’ve held events to reduce stigma amongst people living with HIV, because we also have self-stigma, and the broader community in the South.

HE: What ways can education be tailored to stigma-related concepts in HIV/AIDS?

CC: We need to update and keep, like, current standards for how we are talking about HIV. Because so much of it, in an educational sense, comes from a historical perspective. We just talked about HIV/AIDS in the 80s, people still see it in that context. They think about the AIDS blanket, they think about the movie Philadelphia, like, so much of our education stopped in 1992. I don’t think that we need to go back to what it used to be, which was scaring people, scare tactics don’t work for education. We need to show people what it looks like to have HIV today. It’s no longer emaciated men laying in hospital beds covered in lesions, it is no longer a death sentence, it is no longer a gay man’s cancer or gay man’s disease. We know way too much about it now. So let’s talk about it. Let’s talk about the fact that we have an alarmingly high rate of cis-heterosexual women who have HIV today, and they are black women, a majority of them. Let’s talk about children who are being born positive. Let’s update and educate people on what it is, what it means to have it and how you can get it, that’s what we could do to break the stigma.

ET: I personally think education about and around HIV should be in just normal everyday conversations. I believe we reduce the stigma by making HIV a part of comprehensive sex education talks, a part of regular health checkups, a part of regular conversation where we’re talking about reproductive justice. If we make HIV a regular part of those conversations, we reduce stigma in every way.

HE: Do you think of yourself as an HIV advocate? What makes you an advocate?

CC: So, here’s my issue with the words advocate, ally, all of those. It’s up to the person who is in need of the allyship or the advocacy to define it. I can’t define whether or not I’m an ally or an advocate. Only those who I am advocating for and being an ally of can say whether I am an advocate or an ally, because I could have the best of intentions, but I could be doing more harm than good, or I could just be getting it wrong. So, I’m always cautious to answer that question about anything, because I’m just what I would hope everyone is, which is a citizen of the world and of humanity. I do not identify as one, I would like to think that, hopefully, I am identified as one by those who need it.

ET: Absolutely, living with living with a chronic illness requires me to advocate for my needs, my rights, my health. Also, because I care and love people, I’m going to automatically want to help other people out. So, I also fight for the rights of other people living with HIV because I understand the struggle of not receiving quality care or services and understand that not getting what we need can be detrimental to your health. It can be life changing. And it could be to the line between whether you live a good life or live a bad one. So, I consider myself an advocate because I fight, advocate and speak up when things are not right, when injustices are being made and when there is progress or good things that are happening. I like to share anything that I learn to help make another person’s walk that much easier if possible.

HE: What work are you currently working on to support those living with HIV/AIDS?

CC: The work I’m doing is trying to educate the general population, specifically, the young millennial generation, who identify as same gender loving men/women and minorities, on what the virus is and isn’t, what it does and what it doesn’t do. The goal is to try to educate them that HIV is not a death sentence. Now, you can be undetectable and not transmitting and that’s a wonderful breakthrough that we’ve made in humankind. However, that does not mean that you should just be complacent in contracting it. Because while HIV is no longer the death sentence that it was when my uncle contracted it. What it is, is it’s a virus and if we’ve learned anything, like with COVID-19, it is that viruses adapt and mutate. So that’s why we need to lower and stop the spread, and hopefully to find a cure for it. So that is what I’m trying to do as an advocate, because I am not a person who personally is living with HIV. So, I try to steer clear of talking about the lived experience and the lived needs because I don’t have it and I can’t speak to that, I can only speak to the facts.

Documentary that Evany Turk will be previewed in

ET: I own my own consulting firm now. I’ve come from all of that and done all of that, to wanting to do more work with black women living with HIV. I decided to branch out on my own, I started consulting with organizations, public health departments, community-based agencies to work on specific programming for women living with HIV. Because I believe if we cure women living with HIV if we if we reach and get all the women living with HIV and care, that we help everybody. So, I started Heartworks Consulting and I named it that, because when I do my best work, it comes from my heart. So far, I’ve worked within 5 states and with 3 different organizations. In a year I have put on 4 HIV educational events, which reached at least 200 women.

There are many women, individuals and organizations working and living each day to reduce stigma, educate, and provide resources to end the HIV epidemic. Candis and Evany are two of many women who are doing tremendous work to support those living with HIV. Women have the ability to create a support network of understanding that transcends race, gender, and social boundaries. By uniting as a collective whole, women have the power to create change. Whether it is through advocacy, public awareness campaigns, policy change, or individual action, women have the potential to make a real difference in the fight against HIV and further empower those living with the disease. It is only through sharing stories like these and working collectively together that we can truly hope to one day put an end to this epidemic.

As Evany Turk said:

“I believe that community is the reason why HIV stigma is not as bad as it used to be. Community is the reason why we’ve had so many advancements and improvements”.

Atlanta, Georgia (November 30, 2018) – In recognition of the 30th anniversary of World AIDS Day and in support of

Our first contributors need no introduction. Well-known in their respective fields, Patrick Sullivan, PhD, DVM, Nic Carlisle, JD, and Samira

Column By: Tiffany Smith Tiffany lives in Atlanta, GA and works with the Emory COMPASS Coordinating Center. She previously worked

Column By: Tiffany Smith Tiffany lives in Atlanta, GA and works with the Emory COMPASS Coordinating Center. She previously worked

©2024 Emory University, Inc. All rights reserved.

When you click this link, you will be directed to an external webpage hosted by LearnUpon LMS.

Kindly note that registration is required, and it’s entirely free of charge.

To access the learning modules, you will need to create a new login, as this platform operates independently and is not affiliated or connected with OpenWater or any other platforms used by the Gilead COMPASS Initiative®.